"I became interested in lighting design while in my high school drama club,"

says Linda Essig.

"Designing the lighting for our productions provided an outlet for combining

my interest in art and literature with my interest in math and science. Once

I got a taste of professional theater as a summer intern following my sophomore

year of high school, I was completely hooked."

Essig entered New York University under an early admissions program to

pursue a combined bachelor's-master's fine arts degree. "This is not a course

I would recommend to most people today," she says. "Instead, I would recommend

a broad-based liberal arts education to be followed by more specialized graduate

school."

This path worked well for her, however. Now, she is a professor of lighting

design at the University of Wisconsin. "I was on a trajectory that led me

right from the sophomore internship to working as a lighting designer professionally.

Becoming a professor came a bit later as I assessed my lifestyle and artistic

priorities."

She doesn't feel that a career in lighting design will make anyone rich.

But there are other benefits to the job. "I look forward to going to work

in the theater or in my studio and enjoy my creative work -- money can't buy

that!"

|

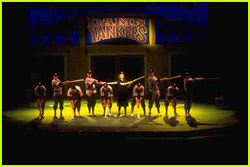

| Lighting designers work hard to make sure the audience gets the right

impression of each scene. |

| Courtesy of Michael Abrams |

One thing she finds satisfying about her career is that the end result

is obvious. That's not available in every profession.

"I love being in the theater and watching what was abstractly just some

marks on a piece of paper indicating an angle or position of a light become

the environment for a play or opera," she says. "I particularly enjoy working

on plays that enable me to design environments very specifically, and to work

closely with the actors on how they relate to the lighted environment."

There are always downsides, of course. "Any personal frustrations I feel

are usually technical in nature -- a piece of scenery is not ready in time,

for example. The other, larger frustration, that I am sure is shared by many

in theater, is with the lack of funding for the performing arts in this country."

Brian Sickels is a professor of theater at East Stroudsburg University

in Pennsylvania. "I chose theater as a career because it was my passion, and

still is. I chose teaching because of my love for students," he says.

"My training began early. I had an interest in theater as early as high

school. My interest continued as I pursued both a BA degree in theater and

an MFA degree in stage design and lighting. However, much of my growth occurred

in the professional theater."

Sickels also talks about the satisfaction of being able to experience what

his work produces. "I like the challenge of creating something from nothing.

I like the challenge of bringing literature to life."

In spite of occasional frustrations, which he says at times have made him

want to quit the business, he is challenged by the work. "Ultimately the experience,

whether good or bad, keeps one coming back."

Bill Williams has been a lighting designer for many years, ever since he

trained in New York City with Broadway theater professionals. "I am always

making new discoveries and having new experiences," he says. "The key is to

keep learning, and to keep an open mind to emerging technologies."

Jill Klores is a senior lighting designer. "I didn't choose this career

exactly," she says.

"I always knew I was interested in architecture, but I did quite well in

the sciences in high school, especially physics. So I went into college with

a major in physics. I soon discovered that wasn't for me. I liked the optics

part of it, but not the mechanics."

She took some time off and went back to a different school and tried some

art and photography classes. But she found there was not enough discipline

in them for her. "I wanted more instruction, more critique. So someone told

me to go to the architecture department. I should've gone with my childhood

instincts all along," she says.

"While enrolled in the architecture school, I took some building systems

electives in the engineering school and found I really liked the lighting

component. So I took as many of the lighting specialty courses as I could."

She feels that her education at the University of Colorado did the trick

for her. But she says many people learn it all on the job. "There's still

a lot of on-the-job training for me. This is not the kind of career where

you can learn most of it in an academic environment, and then go out there

and be a lighting designer."

Klores is one of the lucky people to have found a career that makes her

happy. "It truly mixes the art and the science that I feel inhabit the two

halves of my brain. It is rewarding to see a job complete, and to learn from

every finished product. The process of taking a client's idea or desire to

the drawing board, through the details, and to the on-site adjustment and

fine-tuning is extremely satisfying."

"To be successful in this field, a person needs to be a good listener and

have the ability to get along with all different kinds of people," says Andrew

Lee. He is a lighting designer and salesperson.